Teachers are often combating student negative self-talk, and I think there are times they say something without realizing the damage it's doing to them. I had a student who, at the beginning of the school year, would preface every comment with "This is probably wrong, but. . .". Was it wrong? No, it was his opinion and perspective? Did that perspective sometimes need more evidence? Sometimes, but his thinking was "wrong."

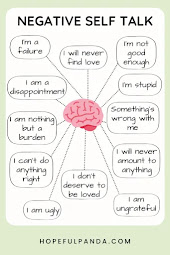

Students learn to say "I'm so stupid" when they struggle with something. Is every student adept at math? No. Does that make them stupid? No, it makes them less adept at math than the person who thinks calculus is amazing. Is every student a great writer? No. Does that make them stupid? No, it might mean they haven't figured out they should take that time to go back to proofread their work to fix those fragments or they haven't taken the moment to learn how to recognize a fragment. A student's struggles with something in a content area doesn't make them stupid or bad at that thing, it just means they are struggling to learn that thing and that they're probably putting too much pressure on themselves because they are also comparing themselves to parental expectations or their friends or the teacher isn't very good at coaching or the student hasn't focused enough on learning that thing or. . . . the list goes on and on and could be a combination of a bunch of things. But being stupid isn't one of them.

The other day I listed to a podcast episode about the inner game, which led to how an entire industry of inner mind coaching has developed to combat the inner critic but also just to help people learn. Because the original focus on the inner coach seemed more about focusing on the learner than the instructor.Tim Gallwey seemed to be a typical tennis instructor when he first began. As I listened to the podcast, I was reminded of my experience with a golf instructor.

My somewhat short aside. The first time I played golf I was in college and went out with two of my roommates, one of whom was at USF, Tampa on a golf scholarship. We were just out. I was doing okay although I have zip recollection of the score; we were having fun. Somewhere on the back 9 a guy on a golf cart shouted out a pointer or two. The rest of the game was less fun for me. Fast forward some years later and a friend of mine and I would go to the driving range; she had base privileges at the time at Patrick AFB in Satellite Beach, FL. I think she actually played golf, but I was fine going to the driving range and whacking balls as hard as I could and as far as I could. Fast forward some more years; I was (and am) living in IL. Another friend of mine and I decided to go to the driving range; she actually played occasionally as part of a foursome and wanted some practice. I'm in my happy place of whacking balls as hard as I can as far as I can. It's a good stress reliever, that. Then she suggested we take lessons. Okay. Sure. My first lesson the golf instructor was on and on about my head, my chin, my hips, my knees, and I don't even know. But I do know I left that day with blisters, in spite of the golf glove, and incredible frustration. I haven't touched a golf club since.

However, as I listened to the podcast, I also reflected on my approach as an educator and as a coach. I'll just say there were some revelatory moments.

The Coach in Your Head is a really good episode, although it does come with a language warning. And there were some bits I will fast forward through when I listen again as I, personally, didn't find the on-demand coaching bit all that helpful. However, the parts with Lewis's daughter I found really interesting.You might also watch this MasterClass with Tim Gallwey or this TED Talk with Brett Ledbetter who interviewed 15 coaches who had over 8,700 wins and 21 national champions among them to learn that "they focus less on the result, more on the process, but they recognize that character is what drives the process which drives the result"

- We do a disservice to our students when we model something and say something like, "See how easy that is?" It may be easy to us but it may still be opaque to some of our students. We need to be mindful not to give more fodder to their inner critics.

- We need to help students focus less on the outcomes and more on the process. That's an uphill battle for many of us because of benchmarks and testing, but we all know in our teacher hearts that if students learn the process of solving that particular calculus problem or if they really understand the events that informed a particular historical event or if they have developed strategies to recognize active voice and identify rhetorical choices, the outcomes of their work will be fine. AND, even more important, they will have established a foundation on which to continue to build as they continue to build.

- Because learning should be, I think, about the process of learning.

- As we continue to help them develop those skills and strategies and figure out the process, we can also help them learn to quell their inner critic.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.